Scotland’s Year of Stories

Heaven and Hell, Stories

of hope and despair in Kinross-shire

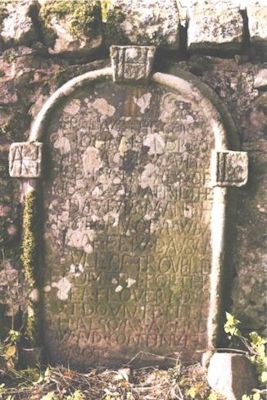

The headstone records that Robert Stirk and his family were exiled from Kinross-shire for 5 years.

The image of

John Knox's pulpit, Glenvale is evidence of the lengths people would

go to in order to worship as they wished

Download the .pdf leaflet Pages

1 & 4

Download the .pdf leaflet Pages

2 & 3

Link to the work produced by local children for the exhibition

The Covenanters'struggle in Kinross-shire

Did you know that

some 350 years ago the local people in Kinross-shire were hunted and arrested,

fined or sometimes put in prison by the soldiers of the King’s army?

All across the lowlands of Scotland people were ill-treated and lived

in fear, and this continued on-and-off for around 50 years.

It started when the king ordered changes in the Church of Scotland which

the people would not accept. In those days the church was at the heart

of Scottish life, and everybody attended the service each Sunday. Every

county in Scotland was divided into parishes, each with a minister appointed

by the laird, who looked after the church helped by a group of elders,

the Kirks Session. The king ordered that the Church would have bishops

in charge instead of the local groups and a new prayer book was to be

used in church services. It would be a crime, punishable by death, not

to obey the new rules. However, many thousands of people objected and

signed a new document – the National Covenant – which declared

respect for the laws of Scotland but insisted that God was the head of

the church, not the king. Those who supported the Covenant were known

as Covenanters. The king was furious at such disobedience and declared

war on the Covenanters, making their lives very difficult over the next

fifty years.

All over Lowland Scotland, including Kinross-shire, ministers refused

to accept the new ways and were thrown out of their parishes and forbidden

from holding services. Some took to holding secret services in houses

and barns locally or out in the countryside in the open air; these were

called field preachings. Troopers (soldiers) were sent to scour the countryside

for these meetings to break them up and arrest those attending. A popular

spot was Glenvale, the secluded valley behind Bishop Hill where there

is a natural rock formation called John Knox’s Pulpit; here ministers

could preach to those gathered, whilst look-outs would be positioned on

the surrounding hill tops to warn of the approach of any troopers. These

meetings drew people from a wide area – Cupar, Kirkcaldy, Saline,

Dollar and even Perth.

Those caught at these meetings could be arrested and fined or put in prison.

In later years they could be executed or transported to Edinburgh, London

or even overseas. Some men were forced to leave their homes to avoid arrest.

The troopers could seize their possessions, crops or their livestock.

Locally the troops were led by Captain Crawford, known as Powmill, from

the name of his farm near where Loch Leven’s Larder is today. In

1675 the captain and his troopers raged through the county forcing many

to flee. Once a preaching at Glenvale was interrupted by the warning sound

of the horn, and the congregation scattered as the troopers approached.

Old John Gibb, the farmer at Pittendreich was hurrying past Crawford’s

farm, trying to escape, when he spotted the captain in his yard. Gibb

pleaded with his neighbour to hide him and although Crawford was a fierce

and ruthless man, he told the old man to go and hide in the boxbed in

his kitchen, saying “The troopers would never look for a Saint in

Hell.” When the troopers appeared, the captain sent them off down

the road. He was not so generous to others who were arrested and sent

to the tolbooth (prison) in Cupar and on to Edinburgh.

On another occasion the troopers were warned of a secret meeting at Glenvale

and reached the foot of the hill before they were discovered. As they

tried to climb up, stones and rocks were hurled down on them as the congregation

made their escape.

The determination of the Covenanters was so strong that when the troopers

left the country, the secret meetings started again. However, the troopers

returned from time to time to enforce the ban on illegal meeting and the

punishments grew more severe. Robert Steedman, a maltman (brewer) was

one who was hunted but managed to escape. In retaliation, the troopers

broke open the malt loft and removed as much malt as they could, even

taking the sheets off the bed to make more sacks to carry it away. Robert’s

wife was driven from her house and not allowed return for eighteen months,

on pain of more punishment. Others lost their crops which were used to

feed the troopers’ horses or their livestock. Some suspected of

being Covenanters had troopers lodged in their homes to keep an eye on

them.

The struggle of the Covenanters continued until the king died and the

new king allowed freedom of worship once more. In 1690 the Protestant

faith was restored and the traditional church was re-established.

There is a Covenanter’s grave in the old Orwell graveyard close

to the path round Loch Leven. It is a memorial to Robert Stirk, a merchant

of Milnathort, who, with his family, was forced to leave Kinross-shire

for eight years until the restoration of religious freedom. It is an important

reminder of the turbulent years when local people were harassed and lived

in fear of the soldiers of the king.

This event has been supported by the Year of Stories 2022 Community Stories Fund. This fund is being delivered in partnership between VisitScotland and Museums Galleries Scotland with support from National Lottery Heritage Fund thanks to National Lottery players.